Would like to meet: women & Victorian matrimony ads

In 2017, according to a study reported in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 39% of American couples met through online dating. It’s how my husband and I met in 2009. At our wedding half of the couples there had met online.

Almost three hundred years earlier, though, Mancunian Helen Morrison was the very the first woman to place a personal advertisement looking for a husband.

In 1727, Helen was living in Manchester and clearly finding the dating scene tough. And so Helen decided to take advantage of the new trend of placing an advertisement for a partner in The Manchester Weekly Record.

While not new, matrimony advertisements were in their infancy at this time. The growth of newspapers from the late 1600s, had created the classified column: the ideal way for a man to find his next bag of corn, pig or wife. And as the 1700s rolled into the 1800s, the use of personal ads for matrimony was classless: ancient European aristocrats put out calls for teenaged brides with good teeth and small feet; local farmers advertised for a woman from strong stock. And often tasteless: a pregnant widow or a one-legged man.

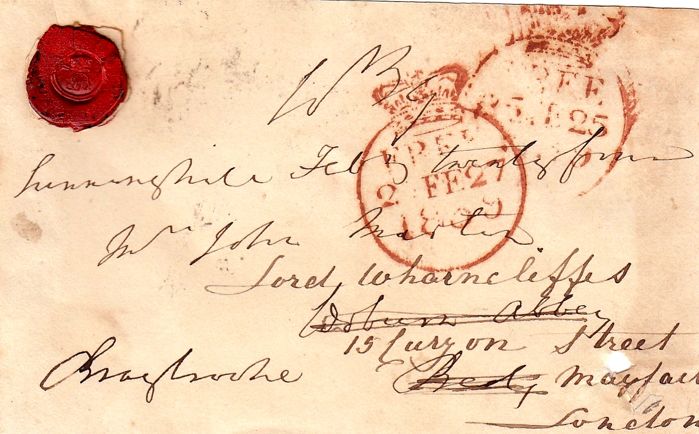

A fascinating insight into how these ads were responded to comes in a rather unappealing way. Six months after secretly murdering his pregnant girlfriend, Maria Millar in May 1827, son of an Essex Squire William Corder placed matrimony adverts in the London papers The Morning Herald and The Times. He received so many responses (above FIFTY from The Times newspaper alone exclaimed contemporary commentators, clutching their pearls) that he didn’t even bother to collect those answering his call in the Times. Instead, on his arrest, the stationer who received the notes on his behalf gave them to reporters and now we have a rich seam of responses which ordinarily would be squirrelled away into obscurity by the recipient.

From the hopeful: ‘I was rather surprised on perusing the Sunday Times, to see an advertisement from a gentlemen, whose age is the same as my own; ’tis strange that a person who possesses a fortune as well as youth, &c, should have recourse to so novel a mode in order to obtain a wife; nevertheless, however odd or romantic it may appear, I agree with you there are many happy marriages accrue from the plan you have adopted.’

To the direct: ‘If you really are included to marry, and all is true which you state, I think I am the person.’

To the seductive: ‘In person I am considered a pretty little figure. Hair nut-brown, blue eyes, not generally considered plain, my age nearly 25. My married friends have often told me I am calculated to make an amiable man truly happy … I am cheerful, domestic of good education and disposition … in a letter like this egotism must be pardoned.’

To the smart: ‘I say nothing of my personal appearance, as I propose occular demonstration.’

But, in a time of such social constraint, how could a respectable woman begin a conversation with a potential suitor without risk to her reputation? What was the Victorian version of constantly refreshing your email for a response?

‘I purpose (sp) meeting you to-morrow at twelve o’clock; I shall be walking towards ____, distinguished by wearing a black gown, with a scarlet shawl, and black bonnet, which handkerchief in my hand: if not convenient to-morrow will be there the same hour Wednesday.’

While contemporary reports thought it was more than reasonable for men to place adverts for wives, the women who replied were clearly shameless old baggages.

‘It could never have been supposed, that so many young women, not deficient in what are termed accomplishments, should be so deficient of that maiden modesty, which is the common and most pleasing characteristic of their sex; as to divest themselves of prudence as well as shame; and, as there is reason to think, enter on the preliminaries of the most important action of their lives, without the precaution of consulting affectionate parents, or experienced friends.’ *

One of William’s respondents’ had something to say on this, though: ‘When a female breaks through the rules of etiquette justly prescribed for her sex, as a boundary which she must not pass without sacrificing some portion of that delicacy which ought to her chief characteristic, it must be for some very urgent reason, such as romantic love, or a circumstance like the present.’

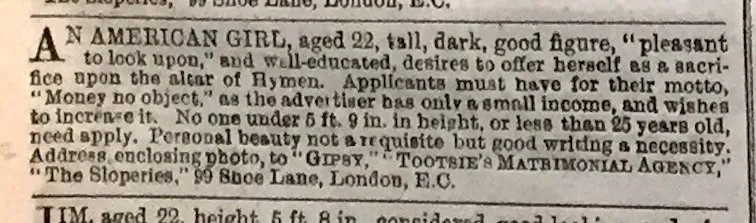

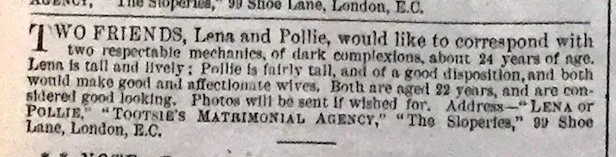

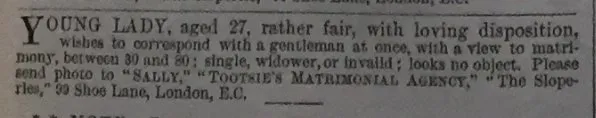

Indeed, women seeking men became far more acceptable as the century wore on and a far more common place for romances/contracts to be discovered. These adverts are taken from the the Ally Sloper Half Holiday comic paper which ran the Tootsie’s Matrimonial Column in the late 1800s.

But what of Helen Morrison, simply looking for someone nice to share her life with? How did she fare a hundred years earlier in 1727?

Rather disappointingly, the only reply Helen received was from the city Mayor who promptly committed her to an asylum for a month.

We’ve come a long way, Helen.

- All of the quotes in this blog are taken from the report ‘An Accurate Account Of The Trial Of William Corder For The Murder Of Maria Marten. To Which Are Added Letters Sent In Answer To Corder’s Matrimonial Advertisement‘ which was published in 1828