The Victorian second-hand clothes market

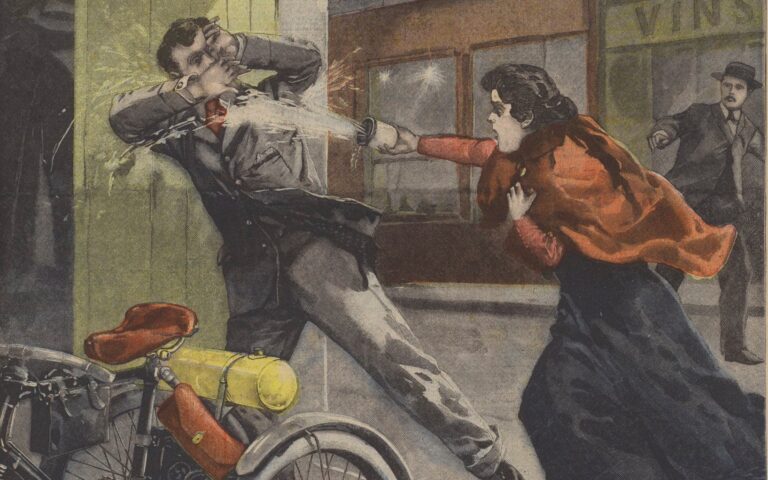

About two-thirds of the way into my current book, my protagonist, Mrs Wood, visits an old friend and Medium who has recently been exposed, a catastrophe that has forced her from comfort and into a room above a second-hand clothes shop in Shepherd’s Bush. I saw this photo recently and it’s exactly as I imagined poor old Mrs Trimble’s downstairs neighbour to look.

While pawnshops were useful for certain items, until the 1870s, second-hand clothing markets such as Petticoat Lane in London or Brummagen Market in Birmingham were the primary source of clothes and shoes for working-class families.

The shops are crammed, and the roadway covered, with articles of clothing in every degree of shabbiness – in every stage of decay. You peer into the dark recesses of the shops, and, rising to the roofs, bulging from cupboards, weighing down shelves, hanging from walls, and littering the floors, are old clothes – nothing but old clothes.The Wild Tribes of London, Watts Phillips, 1855

In the time before mass production, clothes would typically have been made by hand in rich fabrics that wore well. This made them last, and while the condition of each second-hand item depended on how many owners’ hands it had passed through, most of the skirts, dresses, jackets, trousers, undergarments, coats, hats, even umbrellas, heaped on the floor or hung from the beams would have started life in the wardrobes of some of the wealthiest families in the country. A dress made for tea parties in garden rooms might end up being worn to work by a charwoman; a Lord’s jacket worn by a groom for sweeping out a stable. This little anecdote exemplifies the journey perfectly:

This coat, now dangling at Levi’s door, once belonged to a cabinet minister. […] In its comfortable embrace he has slumbered, when borne swiftly along on his road to Osborne or Windsor, the music of the last new opera still ringing in his ears, and a vision of the ballet dancing gaily through his brain; while deep down in the recesses of this breast-pocket, which now gapes so invitingly open, lay the “destinies of Europe” done up carefully with red tape. […]

But we are forgetting the coat., which […] is now an object of especial attraction to a slim, active-looking fellow […]. “Our friend” knows him […] “That’s Dick – Dick Abbot, of the Mint – Downy Dick, as we call him; and a knowing card he is, too; the best hand at a burglary of any in the trade.’ […] Our friend pauses, and we look with increased interest upon this clever specimen of a successful rogue, and then at the coat he is now engaged in cheapening, and fall a-thinking upon the difference of position between its first owner and this ruffian, perhaps its last.The Wild Tribes of London, Watts Phillips, 1855

Only those who had truly given up would be seen in rags. The Victorian’s obsession with cleanliness meant that a presentable dress or suit was essential if a person wanted to be given work. A trader told Watts Phillips: “Poor families, you see, half ruin themselves to get them bits o’ duds together, cos no grief ain’t respectable without ’em; and so they pinches their bellies an empties their pockets to hang themselves all round with crape like a weeping willer […] then, after a time, the family goes to the workhouse, an’ the duds, in course, comes to us.’”1

Clothes were also useful collateral to the poor – when times were especially hard, skirts, dresses, jackets or boots would be sent to the pawnshop to cover the cost of a night’s accommodation or a meal.

But it wasn’t just the local trade that relied on pre-loved: huge amounts of second-hand clothing and accessories were sent to America to support immigrants, while more went on to Australia. And then there were the ‘clobberers’ who could transform a well-worn item into a bespoke piece for the wealthy.

This person is a master in the art of patching. He has cunning admixtures of ammonia and other chemicals, which remove the grease stains, he can sew with such skill that the rents and tears are concealed with remarkable success, and thus old garments are made to look quite new.Street Life in London, J.Thomson and Adolphe Smith, 1877

Indeed, according to the famous documentarian of the working classes, Henry Mayhew, “The thicker the grease, the fresher is the wool beneath, and the “clobberer” can clean up the dirtiest coat in a few minutes.”2

The second-hand industry’s dominance began to fade with the growth of the commercial sewing machine in the 1860s. As important within the industrial revolution as the spinning jenny, cotton gin and steam engine, increased availability of commercial machines saw a proliferation of emporiums selling cheap, ready-to-wear clothes so that by the 1870s, only those with unreliable incomes, or no income at all, came to rely on the second-hand trade. You can see, however, by the clothing Catherine Eddowes was wearing the night she was murdered on 30 September 1888, how important it continued to be. Catherine picked up work where she could sometimes as a domestic, sometimes as a hop-picker, but she had no fixed address, regularly sleeping in London’s east-end casual wards. For that reason, she was probably wearing everything she owned the night she died. The condition of some of the clothes shows how essential these sources remained for Victorian people without means.

- Black straw bonnet trimmed in green and black velvet with black beads and black strings, worn tied to the head.

- Black cloth jacket trimmed around the collar and cuffs with imitation fur, and around the pockets in black silk braid and fur, with large metal buttons.

- Dark green chintz skirt patterned with Michaelmas daisies and golden lilies, with 3 flounces, and brown button on waistband.

- Man’s white vest, matching buttons down front.

- Brown linsey bodice, black velvet collar with brown buttons down front.

- Grey stuff petticoat with white waistband.

- Very old green alpaca skirt (worn as undergarment).

- Very old ragged blue skirt with red flounces, light twill lining (worn as undergarment).

- White calico chemise.

- Pair of men’s lace up boots, mohair laces. Right boot repaired with red thread.

- Piece of red gauze silk worn as a neckerchief.

- Large white pocket handkerchief.

- Large white cotton handkerchief with red and white bird’s eye border.

- Two unbleached calico pockets with tape strings.

- Blue stripe bed ticking pocket.

- Brown ribbed knee stockings, darned at the feet with white cotton.

- The Wild Tribes of London, Watts Phillips, 1855

- The Morning Chronicle : Labour and the Poor, 1849-50; Henry Mayhew – Letter XIV