Did people eat bananas in 1873? or: the importance of research

The Past is a foreign country: they do things different there.

The Go-Between, PJ Hartley

Writing historical fiction is like writing any kind of fiction: your characters have needs, wants conflicts. They move about, travel, visit theatres and zoos, get drunk, fall in love. All the stuff of drama. But the difference for historical fiction writers is that when you set your book in the past, you add another layer which is rich, fascinating, engrossing and really, really annoying.

PJ Hartley had it right: the past is indeed a foreign country. But the problem now is that not only do they do things differently there, the things they do have been so well documented by brilliantly researched books and films that you can’t get away with throwing a banana into an 1873 buffet if they didn’t reach the masses of England until 1880. As a good friend of mine who also writes historical fiction said: every single thing I write, I imagine all these women-of-a-certain-age sucking their teeth and saying ‘I think you’ll find that in 1873 bananas were only available to Marquises and actresses with Ps in their name.’

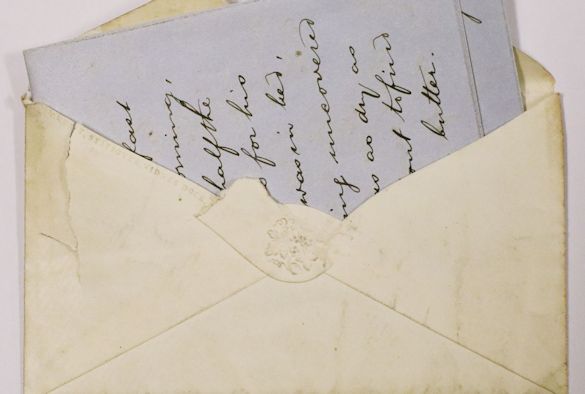

That was why I once lost half a day to Google trying to find out if an English Victorian buffet might include a vol-au-vent. I finally found an English recipe book which included crab vol-au-vents from around that time, so into the buffet they went but in hindsight did it warrant that level of scrutiny? Yes. Because I was sure that someone somewhere would’ve known. Or at least had an opinion.

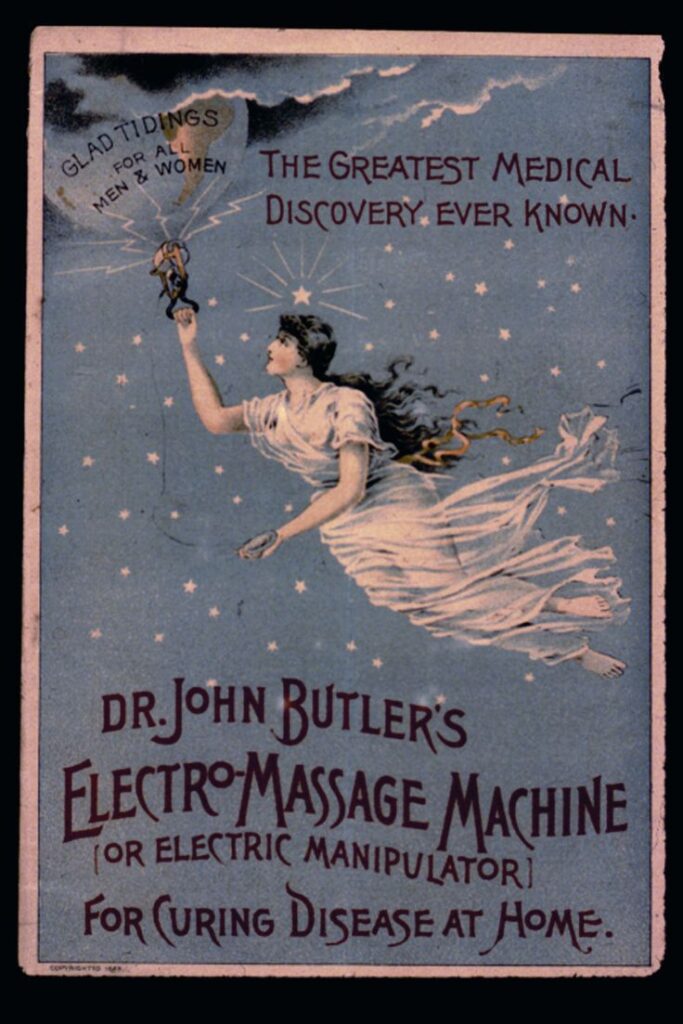

And that’s the nub of it. Because what we know about the nuances of Victorian life is only through a modern interpretation of the documentation left behind. Take clinician-delivered genital massage, if you will. You may have heard that in the nineteenth century, women were taken to hysterical paroxysm (orgasm) by doctors to treat hysteria – a catch-all term for women suffering from health issues related to what was thought to be a wandering uterus.

When first introduced, a doctor had to – allegedly – perform the stimulation manually, but with cramping a problem, the first vibrator was invented and the treatment became increasingly popular. This idea comes from Rachel Maine’s 2001 book The Technology Of Orgasm: “Hysteria,” The Vibrator, And Women’s Sexual Satisfaction. Rachel is a technology historian so her research focused on the machines as much as their application. This idea of doctors delivering stealth orgasms to the buttoned-up women of Victoria’s time captured the public’s imagination, so much so that a few years later we see the film Hysteria released – which, if you haven’t seen it .. imagine a 90min aerial shot of a parade of women’s delighted faces as Rupert Everett and Hugh Dancy use genital massage to its conclusion. Maine’s proposition had become fact.

Fast forward to 2018 when Hallie Lieberman, historian of sex and gender at the Georgia Institute of Technology and author of Buzz: The Stimulating History of the Sex Toy, coauthored a paper called Failure of Academic Quality Control: The Technology of Orgasm for the Journal of Positive Sexuality. This paper challenged everything that Maine had suggested about the use of vibrators in clinical situations. She looked at each of Maine’s sources and was unable to find anything that resembled her claims. She also highlighted that Maine’s work had been cited hundreds of times thus giving the idea increasing credibility, but none of those historians had fact-checked the information they were citing.

Now, for all we know Lieberman could be wrong and all of Maine’s work is substantiated. Or it could be the reverse. Either way, the narrative that remains is the one that caught the public’s attention – the argument around truth makes very little difference now.

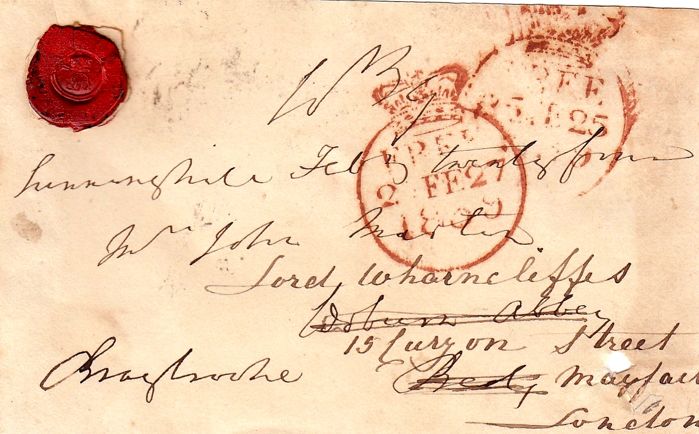

My point of this story is that no matter how much you research something, someone somewhere will have a different opinion. Primary resources are full of contradiction, or, conversely, lacking in precious detail. For example, those nineteenth-century diaries that are rich with day-to-day detail so useful to us historians rarely belong to the working classes. Hannah Cullwick is a rarity in that she was a servant who was a prolific journaler, before and after her marriage to Arthur Munby the ‘philanthropist’ (wealthy white man obsessed with working-class women). But her experiences were unique to her situation: the servant in the house next door would have had a different story to tell.

The importance of research is without question. My point is to be diligent, make sure you get your dates right, understand and know if you could buy a banana in 1873 or how much a dress might cost in bombazine, or if toast was part of a Victorian breakfast. But your story? That’s for you to bring to life through your imagination.

So did people eat bananas in 1873? Yes, but only if they were rich or had contacts at the docks.

With thanks to Michael Hobbs and Aubrey Gordon for their fascinating discussion of the Maine – Liebermann debate on the podcast ‘Maintenance Phase’. Transcript available here: Maintenance Phase Podcast.